The opening of Tim Winton’s new novel Juice cannot help but put readers in mind of Cormac McCarthy’s seminal work The Road. A man, possibly an ex-soldier, and a young girl travel in a vehicle across a blasted future landscape:

The opening of Tim Winton’s new novel Juice cannot help but put readers in mind of Cormac McCarthy’s seminal work The Road. A man, possibly an ex-soldier, and a young girl travel in a vehicle across a blasted future landscape:

So I drive until first light and only stop when the plain turns black and there’s nothing between us and the horizon but clinkers and ash …

I know she’s awake, but the child, slumped in the corner of the cab, does not move.

As with McCarthy, Winton provides spare descriptions of a ruined world:

Gated compound. Battered shipping containers circled into a stockade. Inside, old hangers and mining habs are set out in rows. In the centre a water tower … Functional places are rare, but this vill looks harshly governed. Safety never comes cheap.

But it turns out that Juice is not that book. Well, not entirely. Before long the story becomes something else, more of a tale about how the world came to that point and a kind-of post-apocalyptic climate thriller. And, being Winton, there is also a coming-of-age story buried in there. But more than that, Juice seems to be a working-through of the anger that Winton feels (and has expressed elsewhere) about the state of the world and the possibilities for the future, and a wake-up call for his readers.

The main narrative really begins when the unnamed narrator and his charge are captured by a loner living in an old mine. It turns out the narrator and the man keeping them hostage (who he calls ‘the bowman’ due to his crossbow) both worked for something called the Service, and so the narrator tries to make a connection:

We’re both schooled, comrade. We both know what’s right.

Fat lot of good that did us.

Both still here, aren’t we? As you say.

For the moment.

And so begins a kind of 1001 Arabian Nights style narrative where the narrator tries to bring the bowman around by telling him his life story:

Better to say there are things I need to tell you.

To save your skin.

Improve our odds. The three of us.

So you say.

I need you to trust me …Here. I say. My bona fides.

If you must.

That story starts many years before when the narrator was a child, years after something called the Terror, in which the global order broke down:

Provinces and cantons that had once prospered from order and co-operation slowly lapsed into fiefdoms based on raiding and slavery. It was said every hamlet square and city plaza sported a gibbet … Water became currency, then power itself.

But as a child and then as a young man, the narrator did more than survive. He lived with his tough-as-nails mother outside a small town on the north coast of Western Australia in a self-sufficient set-up that enabled them to trade for the things they needed, moving underground for the hotter months of the year. Winton, being Winton, cannot help including the coming-of-age story of the narrator as a young man who finally gets to go out on his own and finds himself learning the truth about his world and being recruited into a kind of global resistance.

This part of the narrative highlights the weakness of this book. For surely the bowman either is not interested in the man’s childhood or knows most of this if he was in the same organisation. And just as readers are probably coming to this conclusion themselves, Winton casually lampshades the rest of the narrative:

Anyway, where was I? Oh. Yes. Telling you what you already know. Should I continue? Yes.

The narrator pledges himself to the cause when he discovers that the world is the way it is because people made it that way (apparently this knowledge had been lost) and that the descendants of those behind the state of the world are still alive. This then becomes the guts of Juice: the double life that the narrator lives as he goes on missions to kill those responsible for the state of the world, spending his downtime back on the farm with his family. Winton himself, in an interview with the Guardian, calls this final version of the novel, in which a group of well-equipped soldiers go around the world killing people and their families, the toned-down version of the novel.

That story is the story Winton feels he needs to tell: that future generations will feel the need to take revenge against the descendants of fossil fuel oligarchs (who they dehumanise by calling ‘objects’) who have holed up in secret bunkers around the world.

He’s a man, not a god … For all his marvels and riches he’s no better than you. What is he but a creature hiding in a hole? He’s not free. He’s bound. By rock, by his past, by fear of people, by terror at the prospect of justice.

The interesting thing about Juice is that when the book opens, the world is in a dire state but people are surviving. Small communities exist, Australian cities still seem to be functional, there is some trade. But over the course of the novel, the world starts to get worse again. Storms become bigger, the weather becomes more extreme. The narrator works for an organisation that seems to have a staggering amount of resources but rather than trying to do anything for the populace, they focus those resources on seemingly pointless revenge missions. Maybe this is part of Winton’s point.

There is a lot of action in Juice, or at least, descriptions of when action happens, which is a different thing. The narrator talks about his missions and the violence and carnage of them. But it always feels at a remove. This is absolutely a novel of telling rather than showing, deliberately so. But this remove drains what are supposed to be action scenes of some of their potency. They become interesting without being viscerally engaging, which is what they need. It is more like someone telling you about a video game that they watched over someone else’s shoulder.

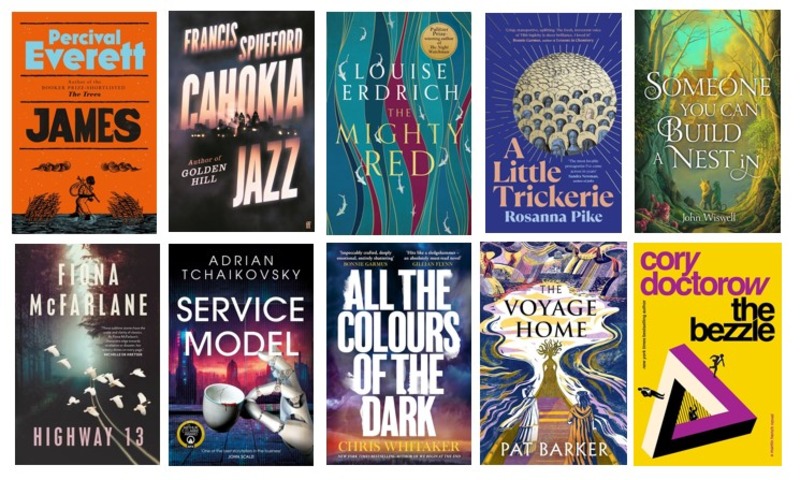

Tim Winton is far from the first author to write post-climate-change fiction. For those coming to this from the science fiction side, the world-building is a bit lacking. The narrator’s mission never really makes a lot of sense. Better examples, for those interested in the genre, are Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower, Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife, Claire North’s Notes from the Burning Age, and Clare Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus.

But the vibe is there. Winton uses his considerable writing talent to paint a vivid picture of a very possible, very difficult future. And, being Tim Winton, Juice will bring a range of readers to this subgenre who otherwise would have turned their noses up (the ‘I don’t read science fiction … but’ crowd). Hopefully this novel will serve as a call to action for those readers who go with him.

As already noted, there is plenty of disaster-infused post-climate-change fiction around already. The more recent spiritual successor of this type of cli-fi is known as solarpunk – a subgenre which more optimistically imagines a post-climate-change world in which humanity manages to move to a more sustainable footing. Rather than making people scared of the future, Winton might have been better off looking to this newer tradition. He has written this book to make people think about the trajectory that the world is on and the interests that are driving us down that road, but not necessarily what they can do about it. Because it is likely that even Winton would agree that while the response he imagines in Juice – taking violent revenge on those responsible for the state we are in – may be one some readers might wish for, it is not one they can really do anything with.

This review first appeared in Newtown Review of Books.

Robert Goodman

For more of Robert’s reviews, visit his blog Pile By the Bed

Other reviews you might enjoy:

- The Coral Bones (EJ Swift) – book review

- The Last Woman in the World (Inga Simpson) – book review

- The Future (Naomi Alderman) – book review

Robert Goodman is a book reviewer, former Ned Kelly Awards judge and institutionalised public servant based in Sydney. This and over 450 more book reviews can be found on his website Pile By the Bed.